Prehistoric Barnum Origins

![]()

Y-DNA testing of known Barnum descendants places our

family within haplogroup R1b1b2 (Western European). This type of test is based

on what are called Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms or SNPs (pronounced

“snips”), which are single-base-pair changes that occur within the DNA of any

given individual. Since these changes occur relatively infrequently, this kind

of testing places an individual in a large deep-ancestral group known as a

haplogroup. Deep SNP testing in its current form may not be directly applicable

to genealogical research concerning recent descendants, since it can only give

us information about our ancestry of thousands of years ago. However, it is

interesting to see the historical migrations of our prehistoric ancestors.

Lineage R1b originated prior to the end of the Last Glacial Maximum (about

12,000 years ago), when it was concentrated in refugia in southern Europe and

Iberia. It is most common in European populations, especially in the west of

Ireland where it approaches 100 percent of the population. This haplogroup

contains the Atlantic modal STR haplotype. Look here

This subgroup probably originated in Central Asia/South Central Siberia and appears to have entered prehistoric Europe mainly from the area of The Ukraine/Belarus or Central Asia (Kazakhstan) via the coasts of the Black Sea and the Baltic Sea. It is believed by many to have been widespread in Europe before the Last Glacial Maximum, and associated with the Aurignacian culture (32,000 - 21,000 BC) of the Cro-Magnon people, the first modern humans to enter Europe. The Cro-Magnons were the first documented human artists, making sophisticated cave paintings. Famous sites include Lascaux in France, Cueva de las Monedas in Spain and Valley of Foz Côa in Portugal (the largest open-air site in Europe).

Later, the glaciation of the ice age intensified, and the continent became increasingly uninhabitable. The genetic diversity narrowed through founder effects and population bottlenecks, as the population became limited to a few coastal refugia in Southern Europe and Asia Minor. The present-day population of R1b in Western Europe are believed to be the descendants of a refugium in the Iberian Peninsula (Portugal and Spain), where the R1b1c haplogroup may have achieved genetic homogeneity. As conditions eased with the Allerød Oscillation in about 12,000 BC, descendants of this group migrated and eventually recolonized all of Western Europe, leading to the dominant position of R1b in variant degrees from Iberia to Scandinavia, so evident in haplogroup maps today.

In human genetics, Haplogroup R1b is the most frequent Y-chromosome haplogroup in Europe. Its frequency is highest in Western Europe, especially in Atlantic Europe (and, due to European emigration, in North America, South America, and Australia). In southern England, the frequency of R1b is about 70 percent, and in parts of Spain, Portugal, France, Wales, and Ireland, the frequency of R1b is greater than 90 percent. Bryan Sykes in his book Blood of the Isles (U.S. title Saxons, Vikings and Celts) gives the populations associated with R1b the name of Oisín for a clan patriarch, much as he did for mitochondrial haplogroups in his work The Seven Daughters of Eve. Stephen Oppenheimer also deals with this population group in his book Origins of the British.

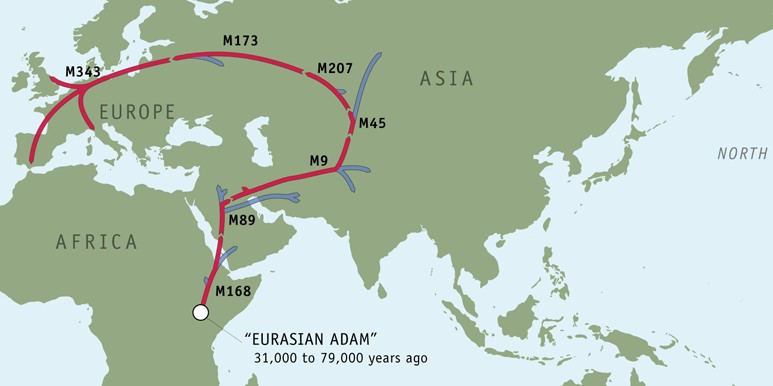

Through what migrations and mutations did our ancestors arrive in Western Europe? The story is an interesting one and with the help of information from the National Geographic Society’s Genographic Project it is narrated below.

There is overwhelming evidence that humans and their hominid (human-like) ancestors developed in Africa and that all humans lived there during the vast majority of prehistoric time.

When humans first ventured out of Africa some 60,000years ago, they left genetic clues that are still visible today. By mapping the appearance and frequency of genetic markers in modern peoples, scientists have created a picture of where and when ancient humans traveled about the world. Those great migrations eventually led the descendants of a small group of Africans to occupy even the farthest reaches of the earth.

It appears likely that in sub-Saharan Africa, some two million years ago, a descendant of the hominid Australopithecus began the direct line of human evolution by evolving into Homo habilis, the first species of the genus Homo. A later species, Homo erectus, living during the Pleistocene epoch (about 250,000 to 1,600,000 years ago), is thought to be a direct ancestor of modern humans. Fossil evidence shows that H. erectus was the first hominid to leave Africa, although that species later became extinct.

Mitochondrial DNA research has identified Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis) as a species distinct from humans, with whom they last shared a common ancestor some 500,000 years ago. Neanderthals were an evolutionary dead end that expired about 30,000 years ago. Rather than giving rise to modern humans, they were most likely outcompeted and replaced by them.

All modern humans belong to the genus Homo sapiens, which first appeared some 400,000 years ago. The emergence of H. sapiens was an evolutionary process, not an event, and it is difficult to pinpoint the exact time when humans became distinct from their most recent ancestor, H. erectus. We do know, however, where that process took place; archaeological and genetic evidence both agree that H. sapiens arose only in Africa.

One particular member of genus H. sapiens (nicknamed “Adam” by scientists) lived in East Africa, in the Rift Valley of modern-day Ethiopia and Sudan. He is the common male ancestor of every living man on the planet today. Adam lived about 60,000 years ago and his descendants were the first humans to leave Africa — which means that all humans lived in Africa until at least that time.

Unlike his biblical namesake, this Adam was not the only man alive in his era. He is unique, however, because his descendants are the only humans to survive to the present day. Adam does not represent the first human, since he had human ancestors. However, there is no remaining genetic evidence of those ancestors and the changes to the Y chromosome that scientists have followed back through the generations to Adam identify him as our oldest common ancestor.

Scientists have been able to pinpoint Adam as our common ancestor because of a mutation that occurred in his DNA (or that of one of his ancestors) somewhere between 31,000 and 79,000 years ago. That mutation (identified as M-168) allows scientists to trace the migrations of Adam’s descendants — migrations that took them out of Africa where they became the first humans to survive to the present day away from the African birthplace. Whatever the reasons for their journey, tracking the descendants of M-168 allows us to chart their path out of Africa and their subsequent population of the entire planet.

Migrations of theR1b1c* Haplogroup

Another male ancestor of the same lineage, born around 45,000 years ago in northern Africa or the Middle East, gave rise to the genetic mutation M-89, a marker now found in 90 to 95 percent of all non-Africans.

While the earliest M-168 ancestors to leave Africa followed the coastal route that led them to Australia by about 70,000 years ago, the M-89 descendants of “Adam” followed the expanding grasslands and plentiful game northward into today’s Middle East. A man born around 40,000 years ago in Iran or southern Central Asia gave rise to a genetic marker known as M-9. The descendants of this direct ancestor of the Barnum family spent most of the next 30,000 years populating the planet.

This large lineage, known as the Eurasian Clan, followed the herds ever eastward over thousands of years, until finally their path was blocked by the massive mountain ranges of Central Asia — the Hindu Kush, the Tian Shan and the Himalayas. Those three mountain ranges meet in a region known as the “Pamir Knot,” located in present-day Tajikistan. Migration through the Pamir Knot gave rise to three separate genetic lineages. Nearly all North Americans and East Asians, most Europeans and many Indians are descended from one of those three.

About 35,000 years ago a group of the M-9 Eurasian Clan migrated north from the mountainous Hindu Kush and into the game-rich steppes of present-day Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and southern Siberia. One of their members developed the M-45 mutation. The M-45 Central Asian Clan gave rise to many more, including those that eventually populated most of Europe and prehistoric America. After spending considerable time in Central Asia, a group from the Central Asian Clan began to head west toward the European subcontinent.

One member of that clan carried the new genetic mutation M-207 on his Y chromosome. His descendants eventually split into two groups, one continuing into the European subcontinent (making them the ancestors of most western European men alive today) and the other turning south into the Indian subcontinent.

As humans continued to move west, a man born about 30,000 years ago in Central Asia gave rise to a lineage defined by the genetic marker M-173. His descendants were part of the first large wave of humans to reach Europe. Their arrival in Europe — and their better communication skills, weapons and resourcefulness — apparently ended the era of the Neanderthals, who became extinct by about 29,000 years ago.

Around 20,000 years ago, expanding ice sheets forced all migration south, into what are today Spain, Italy and the Balkans. Within the group that followed those southern migrations was a man born with the mutation M-343. As the ice retreated and temperatures became warmer, about 12,000 years ago, many M-173 and M-343 descendants moved north again to reinhabit places that had become inhospitable during the Ice Age.

The continued movement westward and northward was accompanied by the development of a mutation known as M-269 — the primary marker of the R1B set of haplogroups. That marker was probably the most numerous among the peoples known to archaeologists as the “Aurignacian Culture”. It is speculated that M-269 descendants were likely the people who created the famous cave art in what are today France and Spain. The M-269 lineages comprise 40 percent or more of the European Y chromosomes today, including Great Britain, where our Barnum M-269 (R1b1c) ancestors settled thousands of years ago.

About 16,000 years ago, near the end of the Last Glacial Maximum, our ancestors began to expand from their Ice Age refuge in what is today southern and eastern France, the Basque Country and the northern coastal parts of Spain, to repopulate Europe. That re-expansion reached southern England between 15,000 and 13,000 years ago, crossing on dry land where the English Channel now exists. Although there was a further contraction of that Stone Age population during the Younger Dryas freeze-up of about 13,000 years ago, it began to expand again at the end of that period, about 11,500 years ago. The descendants of those early colonizers are still onsite today.

Using the Oppenheimer Clan Test for British and Irish origins, Stephen Oppenheimer has determined that the Barnum line is male genotype R1b-12. That type is one of the nearly 50 clusters (male founding clans) identified in his book The Origins of the British. The R1b-12 clan is a sub-cluster of the Mesolithic Basque ancestor Ruy (R1b-10). The clanR1b-11’13, the immediate ancestor of R1b-12, arrived in what is today the British Isles during the Mesolithic period (Middle Stone Age), as mentioned in the paragraph above. That group subsequently gave rise to the R1b-12 clan by re-expansion in the same area approximately 5,000 years ago, during the Neolithic period (New Stone Age).

During the subsequent Bronze Age and the following centuries those early settlers from Iberia received small injections of genes brought by invading Romans, Vikings, Anglo-Saxons and Norman French conquerors— to form the genetic mixture that characterizes the more-modern ancestors of Thomas Barnum (1625-1695), the immigrant Barnum ancestor in North America.

The

information on this site is developed and maintained by

©1998, 2022. The format of this website and all original statements and narrative included on it are copyrighted and all rights are reserved. Factual information may be freely quoted for use in private genealogical research when accompanied by a full source citation, including the date of acquisition. Click here to view the format of a citation for an Internet resource. The publication of large extracts from this site in any form requires prior written consent.